Introduction

Scuba Diving is an amazing sport, but if you talk to non-divers, you may hear one question: “Isn’t that dangerous?” This question, fueled by stories of decompression sickness, equipment failures, and unexpected encounters with marine life, can turn curiosity into hesitation.

The reality is, like any adventure sport, scuba diving does carry risks. These risks can range from “the bends” to environmental hazards, and they can be intimidating for those unfamiliar with the depths. But what if these dangers could be managed and minimized?

In this article, we’ll dive into the common concerns surrounding scuba diving and explore how you can mitigate these risks through proper preparation, reliable equipment, and best-practice safety procedures. Understanding the challenges is the first step towards enjoying scuba diving safely. Let’s begin by breaking down the risks.

Understanding the Risks

Humans are not meant to breathe naturally underwater, so scuba diving has inherent risks. However, with the sport’s increasing popularity, more research has been undertaken into safe diving methods and the risks involved.

Decompression Sickness (DCS)

The number one risk people associate with diving is decompression sickness, otherwise known as DCS or “the bends.” DCS occurs when nitrogen forms inside the body as harmful bubbles in the bloodstream or tissues. Nitrogen is naturally present in the air we breathe but can change its composition and become dangerous if not appropriately managed when at pressure underwater.

So what causes it? Well, water has weight, so the deeper you dive the more pressure that water puts on your body squeezing you from all directions.

Over time, your body accumulates nitrogen build-up, which must be reabsorbed slowly to avoid bubble formation. Surfacing too quickly after a long dive will cause nitrogen bubble formation within your body. As the bubbles form on the surface at neutral pressure, they can cause joint pain, skin rashes, and general feelings of light-headedness, along with other neurological symptoms such as headaches and vision loss.

DCS can be prevented by good diving practices. Dive within your no-decompression diving limits and make your safety stop. If you are decompression diving, always follow all safety stops at all depths for the required time lengths, and ensure you are properly trained in diving deco or non-deco before getting in the water.

Barotrauma

Barotrauma is a word used to describe a collection of pressure-related injuries that can affect divers. Here is a quick summary of each type:

Ear barotrauma is the most common type of barotrauma that affects divers. It can take several different forms, from inner ear squeeze to ruptured ear drums. Pulmonary barotrauma affects the lungs and the neck area, this can be dangerous in severe cases. Sinus barotrauma affects the sinuses behind the face between the nose and the ears, this can cause serious pain. Mask barotrauma, also known as mask squeeze, is possibly one of the least serious barotraumas, but it is still a major annoyance.

All forms of barotrauma have slightly different symptoms, but what they all have in common is that something feels wrong when going under pressure, coming up from pressure, or both. This is normally accompanied by pain. To prevent barotrauma injuries, listen to your body. Descend slower or ascend slower, try going back up or down a little until pain and discomfort cease, and don’t be afraid to cancel a dive. Risking longer-term damage for the sake of one dive is not worth it.

Equipment Malfunctions

Equipment failure is a risk involved with scuba diving, but it can be managed with regular checks and maintenance, as well as purchasing quality gear from a reputable supplier.

All scuba gear from a reputable supplier undergoes rigorous testing to ensure it will last well within the specified periods if properly cared for and serviced.

Some common equipment failures that can be dangerous when underwater include blowing hoses from being kinked or worn from chaffing, regulators not functioning correctly underwater, losing weight belts, and having an uncontrolled ascent.

To avoid these situations, make sure you are professionally trained, follow procedures, and get your gear serviced by professionals. We will discuss all these things in more detail later in this article.

Marine Life Encounters

When you are diving in the open ocean you are in the territory of wild animals. This of course can lead to dangers from various sources. Thanks to Hollywood, particularly the movie Jaws, most people think this danger lurks from some giant Shark waiting to eat all the divers in the water. The chances of being attacked by a Shark while diving is extremely rare.

Suppose any marine life encounters could put your health at risk underwater. In that case, they are more likely to be small venomous creatures, such as Stone Fish (Scorpion Fish), Lionfish, Blue Ring Octopus etc, or those ever-annoying Titan Trigger Fish when defending a nest site.

The risk of injury from marine life encounters can simply be avoided or minimised by safely interacting with marine life. Always practice good buoyancy, never touch any marine life, coral or rocks underwater, and don’t stand, kneel or lay down underwater.

The most likely thing to happen is that you will accidently put your hand or knee on marine life resulting in a defensive sting or attack. Avoid this by not disturbing them, and instead observing from a reasonable distance that does not intrude on the animals’ natural behaviours.

Remember that even the very few Shark bite incidents are thought to have happened as the Shark is surprised by the sudden appearance of a diver out of the murk and is more of a defensive move.

Animals underwater do not actively seek you out as food. Remember to ensure the animals do not see you as a threat.

Environmental Hazards

Various environmental hazards exist underwater, all of which can be managed through awareness and good practices. Let us look at three here: currents, visibility, and entanglement.

Currents

Currents can be described as feeling like a strong wind underwater. Underwater though, these forces can not only push you back and forth but can also push you down to depths or up to the surface. An upcurrent or upwelling can be dangerous as it can raise a diver to the surface, quicker than what is safe for decompression times and draw divers to hazards on the surface such as exposed rocks on submerged pinnacles.

Down currents are dangerous as they can suck divers down past their planned dive depth, meaning that the divers may not have the correct amount of air planned for long decompression stops before surfacing, or worse still not be able to surface at all before running out of air.

Lateral currents can pull you right off course and cause you to become separated from your group or taken far away from the dive site, where you can become lost in the boat at the surface, waiting to pick you up. Poor visibility can be caused by several factors including runoff from rainfall on land, storms or strong currents stirring up bottom sediments, or phytoplankton and zooplankton blooms in the water.

Visibility

Whatever the cause, bad visibility can be a hazard. It can cause you to become lost from your group or dive buddy on the dive site and end up in the wrong place, or it can cause you to become disoriented in a confined space like a penetration wreck, leading to entrapment.

Entanglement

Entanglement can occur underwater in several ways, depending on the hazard. Discarded fishing lines, ropes, and ghost nets are all man-made objects that can be present in a natural dive site and increase the risk of a diver becoming entangled and unable to escape or surface from a dive. Even some natural environments, such as kelp forests, can lead to divers’ entanglement. As with anything, though, there are things we can do to mitigate all these environmental hazard.

Number one is to dive with a suitably qualified person who is experienced in the local environment and knows how to avoid the hazards. A good dive guide will have navigated currents in the area they dive. They also know exactly how to read them to avoid dangerous situations.

They will do a current check before a dive and even call off a dive if it is dangerous. They will also know how to avoid entanglement spots and when to call off a dive for bad visibility.

Statistical: How Dangerous is Scuba Diving?

So all these hazards sound a little doomy and gloomy when you read about them, but what is the actual probability of these things happening so I can tell what the actual risk is? Well thanks to organisations like DAN, there is a lot of data out there on safe dives versus incidents so we can assess the statistical safety analysis to know how dangerous scuba diving is, or as I like to think of it, how safe scuba diving actually is.

DAN has conducted studies on decompression sickness and found that:

“In this retrospective study, insurance claims data from 2000-2007 were analysed and the annual per-capita decompression sickness (DCS) incidence rate was estimated and found to be 20.5 per 10,000 member-years.” (Denoble PJ, Ranapurwala SI, Vaithiyanathan P, Clarke RE, Vann RD. Per-capita claims rates for decompression sickness among insured Divers Alert Network members Undersea Hyperb Med. 2012; 39(3): 709-15.)

In other statistics for all types of diving accidents, the number sits as one fatality for every 200,000 dives, 1 fatality for every 120,000 dive hours. This is very good odds for a sport where severe accidents can have very serious consequences and shows the safety of the controls for the sport. It puts Scuba Diving at the lowest end of the dangerous activity spectrum, less dangerous than riding a motorcycle.

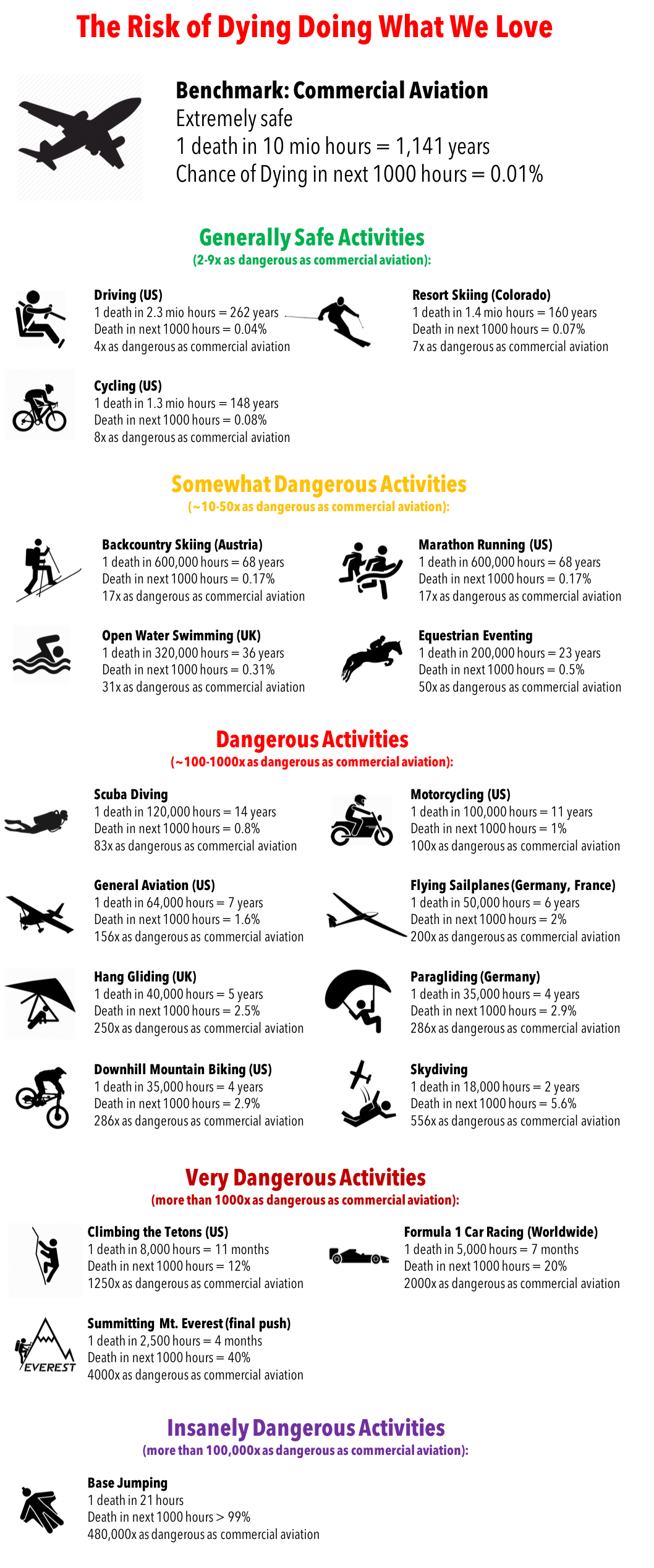

Let us compare this to some other regular and also some extreme sports. Clemens posted an interesting infographic on this topic.

Based on statistics, we can conclude that Scuba diving is not as dangerous as Paragliding, Hang Gliding or skydiving, but is more dangerous when compared to Skiing and Cycling.

How to Reduce Risk When Scuba Diving

Now that we have an understanding of the common causes of accidents in scuba diving, let’s see what measures we can take to minimize the risk of accidents. There are a couple of aspects we can focus on, from pre-dive preparation, using essential safety practices and knowing emergency procedures to handle incidents, just in case unplanned events do happen.

Pre-Dive Preparation

Training and Certification

Scuba diving safety improves with training and ongoing learning. Starting scuba diving requires basic knowledge and skills training. That is what scuba diving organisations like PADI, SSI etc are for: they provide courses and certifications for divers to learn to use equipment, control buoyancy, manage nitrogen loading, handle equipment failure, and manage currents.

This background information is important. It helps you learn the technicalities of diving, which builds confidence and ensures good decision-making underwater. Without this education, divers might not know the dangers involved and how to react in emergencies, which could lead to fatal situations.

Continuous learning is even more important for divers, and certification is just the start. The undersea world is always changing. Different areas have unique challenges. These include unusual water movements and reduced visibility.

Your Health and Fitness

Though it may look a little lazy when it comes to comparing the physical effort you put into diving compared to a sport like soccer, being fit and healthy is still a requirement in scuba diving. Here are some health requirements that you should adhere to before you start diving:

Cardiovascular Fitness

Diving can be intense at times, particularly when against currents or while carrying equipment. Healthy cardiovascular status assures the body of good physical capabilities to manage the strenuousness of diving, minimises the risks of overexertion, and assists in effectively coping with breathing in the water.

Respiratory Health

Your lungs play a critical role in diving because you breathe through a regulator underwater. It is vital to ensure that they are healthy and do not have any respiratory conditions, such as asthma, which might cause some hitches while underwater. Any condition that affects breathing can be hazardous underwater, where proper breathing techniques are vital for buoyancy control and conserving air.

Ear and Sinus Health

It is essential to equalize pressure in your ears and sinuses when descending and ascending while diving. If you have a cold, congestion, or infection in the ear, equalizing pressure can be quite tricky and painful, which may lead to injuries like ear barotrauma. Listen to your body. If you doubt your health, postponing your dive until you get better is always advisable.

Dive Planning

Always stick to the dive plan. Do not go off somewhere else because you see something interesting at the peril of the environment around you. Even if the visibility is bad, listen to your dive guide or dive buddy, stay with them, stick to the plan and call off a dive if it is too hazardous. Also carry additional tools such as a SMB for the boat on the surface to see you in high current, an underwater flashlight to see your group in bad visibility, and a dive knife to free yourself from any entanglement.

Utilize Essential Safety Practices

Buddy System

The buddy system ensures that the diver has someone else underwater with them. This system enhances safety because there is always immediate help if there is an emergency. Your dive buddy can also share their air supply, help with equipment failure problems, or even offer physical assistance, which dramatically lowers the risk of a more serious accident.

Another critical aspect of the buddy system is that each diver is monitored and has situational awareness throughout the dive. This mutual vigilance keeps small problems from escalating into big problems.

Also, diving with a buddy enhances the overall experience as it’s social and rewarding. You can share the excitement of being underwater, point out interesting marine life to each other, and make some great memories to discuss over a beer after your dive. In fact, these are the joys that dive buddies share among themselves to increase diving fun.

Monitor Your Air Supply and Depth

In simple terms, your air tank is your lifeline beneath the water’s surface. If you don’t monitor your air gauge regularly, there’s a good chance you could run out of air before you know it, and running out of air can cause a situation that just might take your life.

By watching your air, you will ensure that you have enough to complete the dive, make any required safety stops, and then safely ascend. Running out of air may be related to panic, resulting in ascents made too rapidly, which can cause decompression sickness or other serious injuries. Checking your air supply at intervals enables you to control your breathing rate and to amend your dive plan if necessity dictates, so you always keep a good reserve of air.

Equally important is monitoring your depth because the greater the depth, the more pressure on your body the more air you consume, and the more nitrogen your body takes into the tissues and bloodstream. The increasing pressure while you descend makes you use up your air very quickly. In addition, some depths have safety implications: such as the control of nitrogen absorption in the body to avoid an incident of decompression illness, sometimes known as “the bends.” Going deeper than you intended without knowing how deep you are means you may exceed your no-decompression limit.

If that happens, you can find yourself forced into a controlled ascent which has decompression stops. These stops are particularly important since they allow excess nitrogen to leave your body safely. If not, bubbles could form in your tissues or bloodstream and cause discomfort or injury. This brings us to the next essential safety measure we can make: controlled ascents and safety stops.

Controlled Ascents and Safety Stops

Controlled ascents are important because, as you ascend, the pressure around you decreases, causing the gases (mainly nitrogen) that were absorbed into your body under pressure to come out of solution. If you ascend too quickly, the nitrogen may not have enough time to be safely released through your lungs.

Instead, it can form bubbles in your tissues and bloodstream, leading to a condition known as decompression sickness. This condition can cause severe pain, paralysis, or even be fatal if not treated promptly. By ascending slowly, typically at a rate of no faster than 9 meters (30 feet) per minute, you give your body the time it needs to safely off-gas the nitrogen.

Safety stops is an additional precaution taken during your ascent to further reduce the risk of decompression sickness. A safety stop usually involves pausing at a depth of about 4.5 to 6 meters (15 to 20 feet) for three to five minutes before completing your ascent to the surface. This stop allows extra time for the nitrogen to safely dissipate from your body, especially after deeper or longer dives where more nitrogen has been absorbed.

It is a standard practice that provides a buffer of safety, ensuring that even if there were minor miscalculations in your dive profile or ascent rate, the chances of developing decompression sickness are minimized.

Moreover, safety stops provide an opportunity to assess your physical condition and ensure that you are feeling well before surfacing. It is also a moment to check your surroundings and coordinate with your dive buddy, making sure both of you are ready to end the dive safely.

Controlled ascents and safety stops are vital for managing the effects of pressure changes on your body, particularly in preventing decompression sickness. These practices ensure that you ascend in a way that allows your body to adjust safely, protecting your health and allowing you to enjoy diving with confidence.

Marine Life and Environmental Awareness

Respecting Marine Life Do’s

Be Observant: Always look at marine creatures from a reasonable distance. A close, slow observation gives us a chance to appreciate some of their behaviours, beauty, and dynamics without interfering with them. This also avoids any danger of startling or provoking wildlife that may be hazardous.

Move Slowly and Calmly: Moving slowly and deliberately is important to ensure that animals do not become scared. Wildlife can interpret fast or jerky movements as threats causing them to run away or become defensive. In this case, slow, calm movement is less threatening within their domain, thus allowing for the continuation of animal behaviour patterns.

Respect: Treat all sea life with respect. Do not touch or pursue animals. Respect the space around them and watch without stressing them out.

Observe Local Guidelines: Abide by local rules and advice on interacting with wild animals in those places where you go diving. There may be new regulations regarding how one should behave towards certain species especially those that are endangered or overly sensitive when trying dives at new locations.

Practice Photography Responsibly: When taking photos, do not get too close to an animal. Flash photography can startle some species, so pay attention to your equipment’s specifications and settings. Always keep the welfare of the wildlife ahead of capturing that perfect shot.

Respecting Marine Life Don’ts

Don’t Touch: Touching or trying to take aquatic creatures is awful because it’s bad for them. It removes the protective layer over their skin, moves bacteria from your body to them, and makes them stressed. Some of these animals, like certain jellyfish or corals, may even sting or hurt you if you touch them.

Don’t Feed: Feeding marine wildlife is dangerous as it can cause a change in their normal behaviour, making them dependent on humans for food. It also disturbs their diet. It can result in animals becoming aggressive towards people, which may make them associate divers with being fed.

Follow these do’s and don’ts to minimise risks and assure safe, respectful, and non-intrusive interactions with marine wildlife. That way, you protect yourself not only from potential injury but also keep these wonderful creatures living in the underwater world safe and their natural behaviours healthy.

Expert Tips for Safe Diving: From Real Life Case

So how about some real-life examples of when things go wrong? We have quite a story from one of our experts here at La Galigo, and here it is:

Let me share with you some situations from my diving career. Let us start with when I was doing my Divemaster training long ago in Central America. At this stage, I had around 100 dives under my belt and was 2 months into a 3-month internship.

A bit of experience, but not a seasoned professional by any means, being in an active training status, all the theory and instruction were very fresh in my mind however.

One particular afternoon I was backing up my instructor guiding a group of divers on a site that was an exposed seamount rising to just break the surface in some fairly exposed open ocean. Conditions were rough on the surface and there was a bit of swell and current around.

During the dive briefing, all divers had been reminded that they must stay behind their guide, stick to the group, and stay on the leeward side of the pinnacle to avoid the worst of the current and particularly the back eddies and upwellings on the edges of the pinnacle. The instructor led from the front and I kept an eye on the group from the back. All divers in the group were somewhat experienced, with the minimum number of dives at least around 50 each.

Shortly into the dive, I noticed one particular diver kept straying from the group a bit. I approached her and signalled for her to buddy up and keep with the group.

She gave me the “ok” sign, buddied up and started to stay close to the group. Around 10 minutes later she started to lose concentration a bit again and take off on her own chasing after the marine life she was seeing, again I gave her a gentle reminder to stay with everyone, and she signalled acknowledgment and did so.

Now keeping a firm eye on this diver, around 30 minutes into the dive I noticed her starting to stray off again towards the back eddy and upwelling area of the pinnacle. I quickly went to her and gave her a clear and stern indication of the danger by shaking my finger and using the current signal of a closed fist hitting against my open palm.

I signalled for her to buddy up with me and swim in the safe direction, and she did so. Not 5 minutes later I had taken my attention off this diver to attend to another, and I saw her wandering off into the dangerous zone again. This time I quickly finned over to her as her attention was off elsewhere and she could not see me signalling to her to head over to the rest of the group.

My attempts were too late, however, and now not only was she caught in a powerful up current but so was I no matter how hard I finned. We were both pulled close to the pinnacle and up through the water column, unable to see anything in front of me from the turbulent white water as we shot to the surface.

We had been at around 15 meters and would have shot up within about 5 seconds. We were only lucky that neither of us smashed our heads on the rocks on the way up or at the surface.By the time she had seen me signalling her, she was already caught in the strong current and was struggling to move.

I approached her and grabbed a hold of her BCD around the shoulder to fin hard down towards the group and try and pull her out of the upwelling back eddy.

The dive boat at the surface quickly saw us and got us onboard. We were administered breathing oxygen in case of any DCS risk and monitored for any signs. Luckily again, neither of us developed any signs or symptoms and we managed to dodge another bullet there.

- Nick Barr

So what’s the lesson here? Listen to the dive plan, stick to the dive plan, listen to the dive guides, follow the dive guides instructions, and stay aware and do not wander off by yourself.

In scuba diving, things can go wrong very quickly when we are in an uncontrolled natural environment like the ocean. Do not become complacent and you can have safe and enjoyable diving all the time.

Not becoming complacent applies to your gear checks too. You may start to get hundreds of dives under your belt but don’t start to forget the basics. You may think you know your gear like the back of your hand since it’s yours and you have used it so many times, but this comfortability with your own gear can be dangerous if you just always think it’s going to be fine because it always has been fine.

Small tears on BCDs can wear away over time if you are not checking it all over. A kinked regulator hose tucked into your BCD can develop a small stress fracture that can lead to a blowout over time. All these trivial things can add up so it’s essential to give all your gear a proper look over regularly no matter how well you think you may know it. Some things can even come up and break from one dive to another.

Conclusion

To wrap this up, the most important aspect to your safety lies in the preparation. That could be from doing your dive training and certifications. Do the research on where you are going diving to be prepared for the unique conditions.

Getting experienced guides, and having a good dive plan and briefing, these things are all as important as each other in the dive preparation stage. This also extends to equipment prep, from selecting the right gear for the type of dive to making sure your gear is all in good shape and set up correctly.

Dive safety really determines a lot of how dangerous diving can be, and that is all determined by how you are prepared physically and mentally to take on that dive. Follow the rules, follow the procedures and have fun doing it and your dive can be a safe dive every dive.